HSV History

31.03.20

Founding fathers: The early years of HSV

In the first of a series of pieces about the history of HSV, we look back at the early years of the club we know today as Hamburger Sport-Verein, right up until the infamous 'Endlose Endspiel' in 1922.

Every year on the 29th September, HSV fans celebrate the birth of their beloved club, looking back on over 130 years of proud history. However, for the first 31 years of the club’s existence, its members would have celebrated the founding of the club on a different date, and in a different year altogether. This is the story of the early years of HSV in a world of political and social upheaval.

Whilst football can claim to be the most popular sport in the world today, this was far from the case at the end of the 19th Century when HSV’s forebearers began playing football. Football was a game that had become popular in Great Britain, with the Football Association founded in 1863 in England, but it took more than two decades for the game to arrive in mainland Europe and Germany in particular. This was mainly due to the disdainful way in which football, and sport in general, was looked down upon by the ruling class. Gymnastics was the preferred option for the upper classes, as it kept the body in shape ready for military action (a most likely possibility in the second half of the 19th Century), but didn’t have the competitive element of a sport, so that the working classes could be kept in check.

Football was described by gymnastics teacher Karl Planck in Stuttgart as the ‘English disease’: “it is mean, absurd, ugly and unnatural.” But the spread of the sport couldn’t be contained for long, particularly in places that had a large student population and interaction with British people, who were more than happy to supply footballs and share their love of the game with their German counterparts. Being a major European trading hub, it was no surprise that Hamburg was one of the entry points for football’s expansion into Germany, with clubs starting to spring up in the 1880s in the Hanseatic sea port.

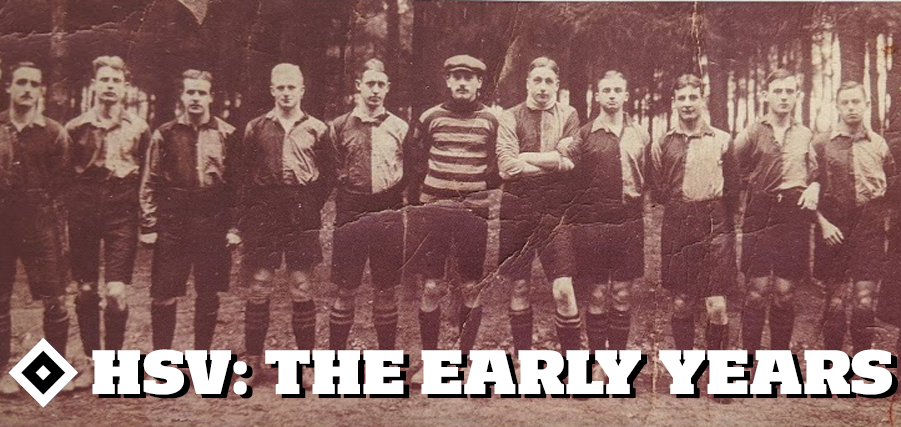

A cohort of students at the Wilhelm Gymnasium were some of the pioneers in Hamburg, setting up the Hamburger Fußball Club (HFC for short) on the 1st June 1888. Membership to the club was fairly restricted and the club couldn’t play as often as they would have liked for a number of reasons. Finding somewhere to play was difficult, with the club playing on the Moorweide next to the present-day Dammtor train station after their inception, whilst footballs themselves and the necessary footwear to play were hard to come by. All of this meant that football was an expensive hobby reserved for the bourgeoisie, and not the game loved by all that we know today. Moreover, the extremely long and back-breaking shifts that the ‘ordinary’ Hamburg citizen would have to put in at the end of the 19th and start of the 20th Century meant that he simply didn’t have the time or energy for sport outside of work, whilst a woman's role in society was strictly limited to supporting their husband.

The First World War was the catalyst for societal change, which also saw football start to become the sport of the masses. With gymnastics only able to keep the troops on the frontline fit to a certain extent, the German generals decided to introduce games of football as a way of keeping morale high and ensuring that their soldiers remained in the best possible physical condition for the gruelling trench warfare. Troops returned from the front having enjoyed the game that they had played and keen to carry on when life returned to normality back at home. Another consequence of the Great War was the revolution in November 1918 in Germany, with one of the many demands from the workers being the introduction of an eight-hour working day. With this change implemented, the working classes found that they had a lot more time on their hands, some of which could be used to play and watch football.

Before the conflict, in 1910, HFC had acquired some land in the Rotherbaum district of the city, which would remain the club’s base until the move to the Volksparkstadion in 1963. The extreme toll of the war, in terms of both lives and money, meant that clubs struggled to survive, and HFC had to merge with two other teams, namely SC Germania and FC Falke von 1906, to form Hamburger Sport-Verein on the 1st July 1919. As SC Germania had been founded on the 29th September 1887, that date was given as the official founding date of the club, in order to make it seem more traditional, with HFC having been founded nine months later in June 1888. As both SC Germania’s and HFC’s club colours had been blue, white and black, these colours were adopted by the newly-formed HSV. The colours were also used in the club’s logo, which has remained largely unchanged to this day, and includes the famous diamond as well as a blue and white background, which bears similarity to the Blue Peter flag signal, both of which are an homage to Hamburg’s shipping background.

Hamburger Sport-Verein’s choice of kit of white shirts and red shorts (hence the nickname Rothosen) was also a nod to the city where the club was based, with Hamburg’s coat of arms painted in red and white. HSV faced significant resistance in the early years of the merger, with the press in particular seeing the choice of colours as HSV claiming to be the team that represented Hamburg, something that they strenuously denied. One newspaper made its feelings clear: “HSV, a colossus built on sand, a bubble ready to burst, will disappear as abruptly as it has been thrust into the public consciousness.”

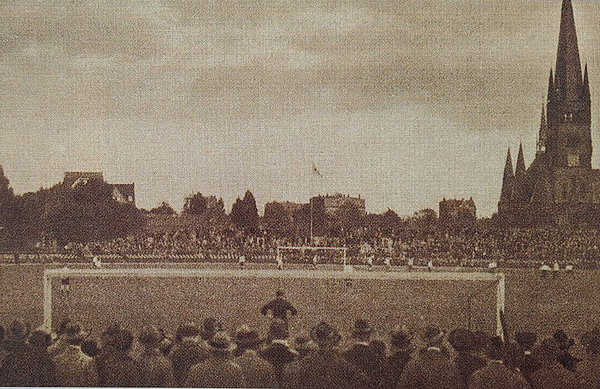

Whilst football was no longer the reserves of the middle class, there was still a strict divide between teams of the bourgeoisie and those of the working man. Based in the leafy suburb of Rotherbaum, HSV certainly represented the former, and, able to pool the resources of all three clubs as well as their financial backers, quickly started to gather a head of steam. This meant the ‘Rothosen’ could attract some of the best talent in the area, with crowds of 20,000 at the Stadion am Rothenbaum rapidly becoming the norm, enjoying some of the best football on offer at that time in Germany. The press’ scepticism that HSV would be accepted by the Hamburg population had proven to be misplaced.

Things rapidly fell into place for the newly-formed club on the pitch, beating Hannover 96 to the North German championship in the 1920/21 season. The Rothosen went one step better a year later, beating Wacker Munich 4-0 to advance to the final of the German championship for the first time in the club’s history. The Deutsches Stadion in Berlin was the venue for the final against two-time German champions 1. FC Nuremberg on the 18th June 1922, a game that would become known as ‘Das endlose Endspiel’, or ‘The never-ending final’. With the score at 2-2 after 90 minutes, the game moved into an extra-time period that had no set limit, and with substitutions not allowed in football until the 1970s, both teams understandably grew increasingly ragged. With the light closing in at 9:00pm, referee Bauwens declared the game a draw after 189 minutes of play.

It took seven weeks for a replay to be organised, during which time the anticipation amongst the HSV fans had grown dramatically. Five trains for Hamburg fans were organised by the club for the trip to Leipzig, with the replay finally taking place on the 6th August 1922. Goals from Träg for Nuremberg and Schneider for HSV meant the two sides couldn’t be separated after 90 minutes yet again. With two players sent off and another player already unable to carry on because of injury, Nuremberg were forced to forfeit the game after the first half of extra time when Popp could play no further part due to injury, as they couldn't field the required seven players.

The DFB’s sporting committee awarded HSV the win in late August, but Nuremberg protested, claiming that referee Bauwens forcing them to forfeit the game was against the law as it had taken place in the half-time interval. On the 15th November, the DFB awarded HSV the title in Jena, ending the longest struggle for a title in German football history, but the Hamburg club refused to accept the trophy, out of sportsmanship for their ‘wronged’ friends in Nuremberg. It only emerged later that the DFB had forced HSV into this compromise. Whilst the conclusion was disappointing, the team from Hamburg were certainly happy with how the season had gone. Not only had the team morally won the title, but the team with the black and white diamond on their chest had sprung to national prominence with their performances against Wacker Munich and Nuremberg. It would be the first taste of success for a club that was only getting started.

Sources: Kinder der Westkurve, HSV Museum, HSV Archives